In Data We Trust: Max Levchin Blows Up Consumer Finance

“So I had this fascinating dinner with one of the CEOs of one of the top three banks in the U.S.,” Max Levchin says, sitting forward in his chair a bit. As the former CTO of PayPal, a sought-after investor, and now co-founder and CEO of Affirm, Max is, of course, no slouch himself. And yet, in a black fleece vest, clutching a glass mug of almond milk with both hands, he could not look more different from a powerful Wall Street banker.

“This CEO said, yeah, you guys in Silicon Valley, you think you’re all kinds of hot. And you’re not! We were the first buyers of mainframes. We had PCs on every desk before PCs were in people’s homes. What makes you think you’re in any way innovative at all compared to us? And we have more money than God, we could buy the latest computers – it’ll be amazing.”

Max holds up his phone. “The CEO literally pulled out his iPhone and said, ‘Do you think my bank can design this? We can design this, and we can do a better job than Apple. Yes, we have more engineers, and they’re more talented, and we pay them better.’”

After a brief pause, Max replies to this CEO as if the man himself were cockily leaning back in the chair next to him.

“Every statement you just made is completely accurate,” he says. “But you don’t rip down everything you’ve built every couple years. Silicon Valley’s as successful as it is because we’re constantly blowing up whatever came before us, ripping it all down and building it back from scratch.” And here, Max smiles.

This statement on the secret of Silicon Valley’s success is no cliche for Max. He lives it, every day. Indeed, his whole life has been a sequence of blowing up the old ways and building anew–over and over and over again. Whether it was emigrating to the States from Soviet-controlled Ukraine as a boy, reinventing how to prevent fraud at PayPal as a 25-year-old CTO, or now creating a new kind of consumer finance for the millennial generation at Affirm, Max has a knack for starting over and meticulously building the next thing faster, smarter, better.

And what makes all of this possible? Data. An ever-growing stream of data that helps explain the past and shows the way to a (hopefully) better future. Data is the raw material for each successive cycle of making and destroying, and, arguably, no one in Silicon Valley is better at harnessing it than Max.

Taking everything he’s learned before at PayPal and Slide, Max shares how he’s now using data to blow up consumer finance at Affirm, his biggest experiment yet. In the process, he’s hoping to make as much good as money.

Paying tuition at PayPal and Slide

Among the many, many stories Max could tell about PayPal, one of the most important is about how he figured out fraud detection. In a recent podcast interview with venture capital firm Andreessen Horowitz (who are, full disclosure, investors in Mixpanel), Max spoke about how, in 2000, he learned the hard way that building anti-fraud software requires “rigor and, for lack of a better term, balls of steel.” It turns out that the only way to stop fraud is to first lose a lot of money from fraud. Just make sure you’re logging your data meticulously along the way.

Max calls this “paying tuition.” When we spoke about PayPal and fraud, he said, “We were going to go out of business unless we learned how to deal with fraud fast, and we had only collected some of the useful data. So, we were trying to build the engine while the plane was crashing.” Every week, PayPal lost millions of dollars to fraud, as Max and his team frantically worked to integrate their data back into their fraud detection models. (It’s no wonder Max notoriously kept a sleeping bag at his office.)

“But because we knew we were going to encounter this [fraud], as long as we had this notion of data-driven stop losses, where we were no longer going to do ‘x’ because we had lost enough money, we would have paid enough tuition.” In other words, if you can gather the data and build the model faster than you burn through your cash, you can (probably) install a new engine into the plane before smashing everything into the ground.

And Max, with his team, was able to build the model in time. PayPal IPO’ed in February 2002, and was subsequently acquired by eBay a few months later for $1.5 billion – leaving Max and the rest of the “PayPal mafia” very wealthy men.

In true Silicon Valley fashion, though, Max and his other PayPal mafiosos – like Reid Hoffman, Peter Thiel, Elon Musk, and David Sacks – didn’t take their newfound wealth and disappear into a sunset of massive yachts, Davos get-togethers, and celebrity friendships (although they have those, too). Instead, they refocused their energies on finding the next industries to tear down and rebuild from scratch.

For Max, that meant a left turn from payments into the fast-growing world of social networks and Web 2.0 with Yelp and Slide, where he was Chairman and CEO, respectively. Both came out of his entrepreneurial lab MRL (which are his initials). While Yelp went on to become, well, Yelp, Slide was a different story. Though Slide started as a way to share photos on MySpace (remember them?), it morphed into the biggest third-party applications for Facebook. Still, being in the hits business on Facebook is a precarious revenue model (just ask Zynga), and Slide never quite took off as planned.

A 2007 New York Times profile of Max said, “[Levchin] chose Slide.com precisely because he thought it had the greatest potential to become a business that could surpass PayPal in size and reach.” So when Slide was bought by Google in 2010 for $182 million, an eighth of PayPal’s price, it was hard not to view that outcome as something of a failure. This time, Max paid the tuition of experience, figuring out that some kinds of challenges weren’t right for his time and resources. Back to the drawing board.

During this period, Max continued to invest in analytics and data-driven companies (like, full disclosure, his early stake in Mixpanel) and serve on the board of major Silicon Valley companies like Yahoo! and Evernote. But, he also fired up MRL Labs again, reviving it as HVF Labs. Standing for “Hard. Valuable. Fun”, HVF promises to search “relentlessly for opportunities that create value by leveraging data”, according to the website. Practically speaking, this means that Max and HVF are looking for potential companies that can be the next catalyst for blowing up the status quo and rebuilding industries like health, information-sharing, and finance from scratch.

Which brings us roughly to the present and Max’s current main venture: Affirm. Max co-founded Affirm in 2013 to “remake consumer finance from the ground up”. How? Affirm provides loans for one-time purchases that would stretch your credit card limit, but are too small for a traditional bank loan. Think new furniture, a mattress, that engagement ring. In the background, he and the Affirm team are building sophisticated credit underwriting algorithms to one day blow up the FICO score.

In Affirm, he might finally have a company that could be bigger than PayPal, and he just raised the capital to prove it: $100 million for a Series D. This time, instead of just tackling one piece of finance, he’s taking on the whole goddamn system –and he has the data to back him up.

Wall Street’s Achilles heel

Remember the big bank CEO who thought that Wall Street, not Silicon Valley, was “the real Innovator with a capital I”? Max believes that he’s found the banks’ Achilles heel: they may be capital-I innovative and able to buy every engineer in the Valley, but they don’t know their customer anymore.

“If you talk to finance people, especially Wall Street people who really understand this stuff, they live in a bubble” Max says. “They don’t understand that regular Americans don’t actually think in bond math.” Banks tend to forget that most of us see lending as a means to an end, not the end in and of itself.

Consequently, most big banks long ago forgot how to communicate with their customers. Max says, “They are dealing with outdated ways of treating data, thinking about it, and presenting data to consumers. They live in a world of their own design.” Wall Street is building a product that makes sense to Wall Street, but not to their users.

It’s from this premise that Max and Affirm have begun tearing down the old financial system and started building a new kind of lending model from scratch. Or, as the mission statement on the website states, Affirm will “deliver honest financial products to improve lives.”

Of course, most banks and financial institutions would say they improve lives. How is Affirm different? Max says, “the biggest thing that differentiates us and our approach to lending is that we fundamentally think that leverage is good but debt is bad.”

He explains with a practical example about when leverage is important: a college graduate preparing for job interviews. “To get a job, you need a nice suit for interviews, but you don’t actually have the money. Typically, borrowing for that is what you do when you get a credit card. There are many, many, many examples when borrowing is a perfectly sensible way of investing in your future, improving your quality of life, and that’s great.”

But what happens when you use a credit card for this purchase? Instead of giving you a one-time way to buy a suit, you end up with a never-ending balance sheet, never-ending debt. “A typical credit card lender, for example, would say, well, it’s actually better if you never pay [your loan] off because then there’s a lifetime of earnings from your balance.”

Max characterizes the traditional attitude of lenders this way: “They are optimizing you as a lifetime customer. But their view of a lifetime is different from your view of a lifetime.” The lenders are incentivized to keep you in a lifetime of debt, even though it looks like they’re increasing your leverage.

Affirm sees it differently. “We’ve basically said, well, if we think of you as a lifetime customer, but a lifetime customer of actual life, you wind up with a lot of very obvious things. Like, we should encourage people to pay down their loan to zero because then they can choose to borrow money or choose not to borrow money later.”

In the process, Affirm has collected data on what makes for a good borrower and can give more favorable rates to that college graduate and others like her the next time they choose to borrow. While traditional lenders use a static, old model, Affirm has created a feedback loop that is constantly improving how they lend.

The biggest tuition check yet? Credit underwriting

Of course, it doesn’t take a financial whiz to see where this is going – Affirm is rebuilding the credit score from the ground up. But if you thought fighting fraud was cash-intensive, rebuilding the consumer credit model is on a totally different level. (And the $100 million Series D starts to make more sense.)

Partially, this is because those who commit fraud are not the same as those who default on a loan. Max explains the difference between fraud and credit underwriting: “One is people lying to you, and the other is primarily people lying to themselves.

“In fraud, it’s actually fairly easy [to detect] if someone isn’t who they say they are: they’ll eventually make a mistake. It’s more a matter of detecting through some behavioral markers what is it that they’re saying about themselves without saying it.

“In credit underwriting, it’s different. Someone has all the good intentions in the world of paying the loan back, but they just don’t actually have the means or they think they’ll win lotteries or they’ll find the money somehow.” How do you know if someone’s good intentions will fall short of their actions? Data.

But, just like with fraud, you have to lose a lot of money first. “So, you essentially have to set aside some of your own budget (that’s your venture capital money that you’ve raised) and tell your investors, ‘By the way, we’re going to spend half a million dollars a year, say, on very risky loans that may have negative returns.’”

Those negative returns come from the edge cases which traditional lenders find too risky. For Max, though, the bigger risk is not to make those loans and lose out on the rich data, good or bad, that they provide for Affirm’s underwriting algorithms. By taking losses now, Affirm will be able to profit later – and lend to many more people who would normally be outside the credit system. This is where paying tuition starts to pay off.

Why UX is actually Affirm’s secret weapon

But Max has also learned that it’s not enough just to educate your investors on how losing money will make you money. Affirm also has to educate consumers about data – something big banks are not known for doing.

“With money, it’s very hard because people typically don’t see complex financial instruments in their daily life until they must understand how they work. So if you’re coming up against a loan type that you haven’t encountered before, you’re kind of a deer in the headlights, not sure what to do next. The most useful thing that we’ve learned is to tell people, ‘Here’s how you think about this.’”

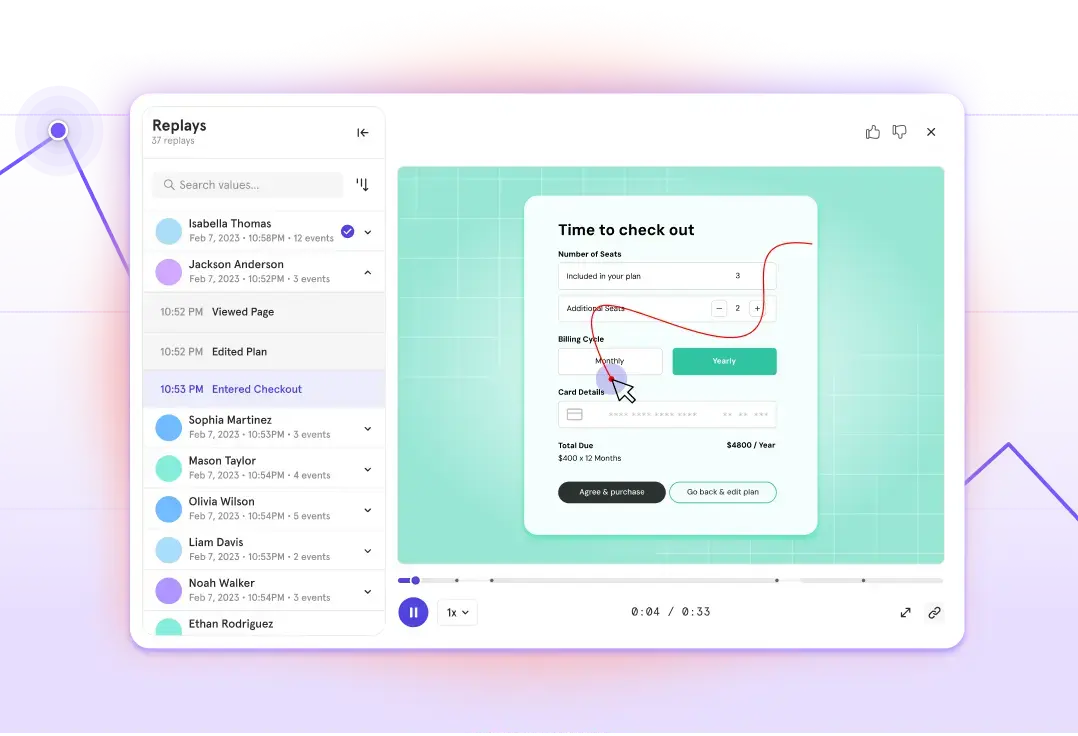

While Affirm’s fancy new credit underwriting algorithms might get all the glory, it is Affirm’s UX research that is really differentiating it from traditional lenders.

“Probably the single most intensely-tested part of our user interface is how we present the loan terms. And it’s probably the single most boring thing for everyone, except the person who’s actually consuming the loans.

“Give the fact the company’s mission is very much to do good in addition to making money, we’ve been obsessing over how to present all the data that goes into the loan. The disclosure forms for a loan are many pages long. So how do you break that down for a phone screen, where people can look at it and say, ‘Oh, I get it’?” What he’s talking about is the fine print. How do you make fine print comprehensible?

Most traditional lenders keep the fine print fine and spend that real estate trying to convince borrowers of why their loan terms are better than others’. These kinds of comparisons depend on jargon like “APR” and numbers with multiple asterisks.

But Affirm has found that this is wrong-headed, and their extensive research demonstrated what probably feels obvious to anyone who has looked into getting a new credit card recently: this stuff is headache-inducing. Max says, “The anxiety that is caused by lack of understanding, at least in our experience, is clearly correlated with people basically saying, I just have no idea what my rate will be tomorrow. If I look at the data from yesterday, I don’t know what it’s going to be like tomorrow.”

So Affirm decided not to put the burden for understanding obscure financial vocabulary on their customers — especially not right before making a big financial decision. “The reality is no one knows how to calculate an APR,” Max says. “What is an APR? Most people don’t actually know what that acronym stands for.” (Confession: I had to Google what “APR” and “bond math” actually meant after speaking with Max.)

“What people really want is to understand that they are being honestly dealt with and that they know what the true cost [of the loan] will be,” Max says. “Telling people that a set of metrics – price, rate, whatever – is never going to change is very, very powerful. As soon as you establish that this data is the baseline, it has an unbelievably comforting effect on people trying to understand data.”

Instead of throwing around industry terms that the vast majority of people don’t understand , Affirm focuses on building trust with clear, user-tested language and design.

Because here’s the thing: It’s not the data itself people are after. It’s the insight into whether or not they can actually afford the suit they need for the interview that leads to the job that gets their life on track.

And this gets back to Max’s underlying principle for overthrowing consumer finance: leverage is good but debt is bad. Can the financial system help people pay tuition towards a better life, instead of saddling them with fees, fine print, and never-ending debt? With Affirm, Max is betting big that it can.

Working for tomorrow

While I was waiting in a glass conference room to meet Max at Affirm’s crowded headquarters in downtown San Francisco, several confused new engineers popped their heads in. They asked if this was where “Engineering 101” was supposed to be (and quickly scanned my face to see if I was yet another new coworker they hadn’t met). It reminded me of most startups I’ve worked at or seen – the scramble for conference rooms, the constant influx of smart new people, the earnestness.

Despite the $100 million investment and Max’s own vaunted “tech titan” status, Affirm is very much like any other fast-growing startup that’s hit upon an amazing opportunity.

“Everyone here is working for tomorrow,” Max told me later. While it would be easy just to take that as an allusion to a startup’s stock options, I know he also meant that his engineers and employees believe they are building something bigger and more important than another hedge fund trading algorithm.

As Max Levchin sees it, data-driven companies can be both for-profit and for-people, and hopefully, Affirm is just one of many.

Next week, we’ll share Part Two of our profile on Max Levchin, focusing on how Max views the tension between the “quantified self” and the right to privacy. To make sure you get it first, sign up below for The Signal’s newsletter!

* * *

Photographs from background imagery by Eli Christman and Tax Credits, and are made available under Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license.