Figma on building usability into powerful products

What do Figma and FigJam deliver to users, and what sort of technical challenges do you face?

Our goal is to help product teams at every stage of the product development process, from inception through retrospectives. I think if you ask the average person in our industry, they'll probably say something like, “Figma is like a design tool,” which isn't wrong. But two-thirds of Figma users aren't designers.

For example, product managers use Figma to review designs, put together mockups, and get ideas down. We also recently launched Figma’s dev mode—a tool built for development—which takes a Figma file and highlights all the things that are important to developers. This helps translate designs into coded products.

Then you have FigJam, which is the collaborative whiteboard tool. People use it to do everything from run meetings to create presentations to facilitate brainstorming, ideation sessions, and more.

How do you balance the desire to have a powerful product with the need to prioritize simplicity or usability? Does that differ between Figma and FigJam?

It definitely does. Figma is a tool that people use to do their jobs, day in and day out, so we need to make sure that everything users could possibly imagine is at their disposal in the tool. We also have the freedom to tailor features to experts in that field, so there's a pretty high bar for power and usability.

With FigJam, we have a goal of trying to make it feel like an extension of your thought process, so it's a really clean user interface. There's a set of basic tools at your disposal, and we really focus on the simplicity element because it’s used by people in a wide range of roles.

For example, suppose a product person is using FigJam to run a cross-functional kickoff for designers and engineers, as well as people in sales who have input or user research. In that case, there's a good chance that some of those people haven't used a 2-D whiteboard or a design tool before. So we use things like skeuomorphic design to make sure that everyone can use the tool intuitively.

When designing a new feature, how do you determine whether you’ve gotten it right?

We approach it in two ways. We have a set of core metrics, for example, high-level metrics for overall retention and usability. Then we have feature-specific metrics so that we can make sure people are using those features at the rate that we want them to be used.

One thing we look at a lot, which is a good indicator of whether a tool is helpful, is whether people are using a breadth or diversity of features. For example, if someone is only using the sticky notes feature, then maybe they think FigJam is just a sticky note tool. But there's a lot more that's available to them, even if we do emphasize simplicity.

FigJam is a powerful tool, so we want to make sure people are getting the most out of it. But we also listen to qualitative feedback, which designers give us a lot of. That’s one of the unique things about working on a tool focused on aesthetics and design.

If you look at what designers are saying on X (formerly Twitter), or the Figma community page, people are giving us feedback all the time. We pay a lot of attention to it because sometimes those individual experiences are pretty important. And when we start to hear themes from this feedback, we react really quickly.

“One thing we look at a lot ... is whether people are using a breadth or diversity of features. For example, if someone is only using the sticky notes feature, then maybe they think FigJam is just a sticky note tool.”

We are also in a lucky position because employees at our company are pretty typical FigJam and Figma users. Everybody at our company runs their meetings in FigJam. People are in it all day. So we get a lot of feedback, and we have a very open feedback culture. Anybody can jump into Slack and just say, “Hey, this feels weird,” or “I would love this,” or “Did this regress?” A good 20% of our jobs is reading, incorporating, and responding to that feedback, which is wildly valuable. It means we can iterate really fast.

How do you balance qualitative feedback versus quantitative feedback? For example, let's say you built a feature that users love, but it drives your diversity of feature metric down. How do you balance those things?

Sometimes we do ship things that we believe in and it might regress an individual metric, and that's okay. As long as the big Key Result (KR) metrics are moving in the right direction, we're willing to make some trade-offs and sacrifices.

The areas where we have no appetite for any sort of degradation are around performance. We had our tech org all hands recently, and our Head of Infrastructure made a point: Performance is like oxygen. When you have it, you don't think about it, but all of a sudden when you don't, it is the most important thing.

So that is an area we pay a ridiculous amount of attention to, with all sorts of regression testing. With every feature we ship, we build in time to make sure it's not going to have any sort of negative performance impact.

What are some of the performance metrics you look at?

Latency is a big one, but the other really important thing we keep in mind is that all of our tools are multiplayer—especially FigJam. Our users are co-creating with people and interacting with them. We have built cursor chat features and reactions and all sorts of stuff that may seem frivolous but are very important for getting people to engage in an interface like this, especially when you have remote teams.

“Micro-interactions can feel like polish or details, especially when you're working on a big-picture feature. But for products like this, those details are the product.”

It’s in the details. If you're editing a sticky and somebody else is adding some content to that or stamping on it and that causes a lag or for your screen to jump or something else—those things are wildly important. Sometimes that's a latency thing. Sometimes it’s the way that the product is actually behaving and which things we prioritize above others.

Early on when I started working here, somebody told me that those sorts of micro-interactions can feel like polish or details, especially when you're working on a big-picture feature. But for products like this, those details are the product. And if those things are not behaving well, people will move on to another product even if they don't know why. It could be like “death by a thousand paper cuts,” and it can be a very real risk with products like ours.

How do you decide to add a particular new feature, knowing it might risk making the product more complicated?

With Figma, there's a little more room for complexity in the name of additional power functionality because we want to make the most powerful design tool possible.

But with FigJam, so much of the “power” is in the ease of use, the discoverability, the virality of it—just being able to invite any person in your company and say, “Hey, jump in this file with us because we want to jam on this idea.”

So we recently did a series of information architecture revisits of FigJam because we felt that the user interface was potentially getting too complicated. If I were to show the “too complicated” user interface to someone at another company, they'd be like, “What are you talking about? There are just six tools on this toolbar, a timer, and this little thing that shows our avatars." But we were concerned that it was just getting too busy.

We also knew that we were shipping all sorts of stuff in the future, and we needed to have a system for where new features would go without jamming them into a toolbar. If you look at a lot of whiteboard tools, it's like their toolbar has 22 features, and then if they add a new thing, like tables or stickers or whatever, they just add it to the toolbar. But that can quickly become overwhelming.

So we focused on progressive disclosure: having a core set of tools in that toolbar, and then, once you opt into one of those modalities, showing you an additional level of detail that’s in line with what you might want to do. It’s not overwhelming. We try to anticipate what people are doing and then give them options to go deeper as they wish.

We use the term “progressive disclosure” a lot. At face value, everything is really approachable. A user may never use particular features, but we want to make sure that that functionality and power are available for people who are trying to do something richer.

How did you decide to have six items in the toolbar rather than more or less?

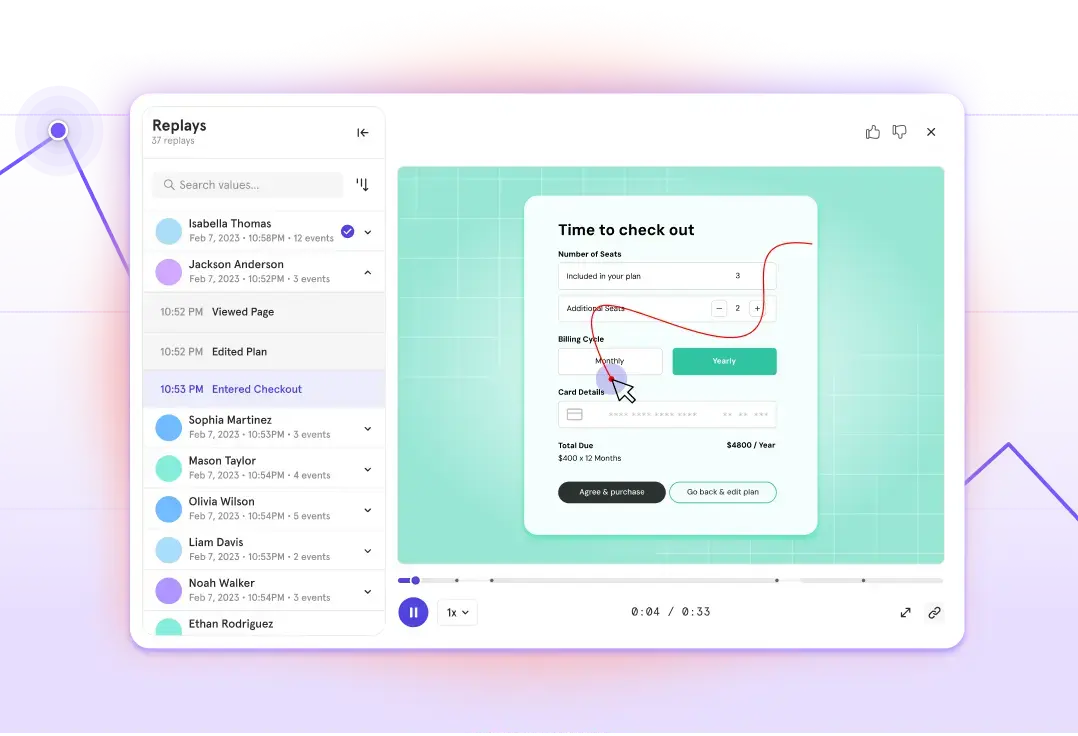

We do a lot of user testing. The most valuable thing that we can do is observe people using the product—whether they are already experts, use a similar tool, or have never used something like that before—and just watch them jump into it. Give them a simple task to accomplish and see how readily they can find those things.

We also look at a lot of qualitative feedback. And we hold ourselves to a really high standard internally. So every single thing that we ship that eventually makes it to users is tested within our own company first.

“If I were to show the 'too complicated' user interface to someone at another company, they'd be like, 'What are you talking about? There are just six tools on this toolbar, a timer, and this little thing that shows our avatars.' But we were concerned that it was just getting too busy.”

At a company like Figma, all of our employees are pretty detail-oriented and into aesthetics. So if we end up pushing anything out that people have opinions on, we hear that very loudly and clearly from everybody.

How do you conduct user testing?

A lot of it depends on how quickly we need to move. If something is lower stakes and we want to get it done quickly, we can find people at the company who are really good use cases for what we're trying to do, especially if we're trying to build something that's targeted at a certain function, like running a weekly kickoff meeting or a planning session.

In terms of external testing, our research team will recruit people who meet certain criteria. Usually, we try to get a range of people with varying levels of technical expertise. And we do a lot of live sessions where we have these people use the tool and talk through their process. We also send out surveys. But as a product person, the most valuable insights come from sitting in those sessions and watching people use the feature.

And if we're being scrappy, we turn to family members or partners who work in tech. Someone might say, “I just had my wife try to do this thing, and she hated it.” So we'll go back to the drawing board.

When conducting user testing sessions, do you test a bunch of things at once, or focus on individual things?

We have a strong research arm, so we're really lucky that we can get specific in what we're trying to test. Every single one of these workstreams kicks off with the question, “What are we trying to learn?” or, “What are we trying to validate?” The more specific an answer we can get, the better.

“We do a lot of live sessions where we have these people use the tool and talk through their process... As a product person, the most valuable insights come from sitting in those sessions and watching people use the feature.”

We do an annual benchmark study where we analyze usability across the board and look for themes and trends. Even here, we tend to be hyper-specific so we can drill down on what we're trying to learn.

How do you measure overall usability at Figma?

For FigJam, our team is sorted into those who work on the core product and those who work on all of the multiplayer elements and details that make running meetings workable. The latter includes things like: the ability for users to hold a vote on various items on the canvas; grouping stickies together; and using a music feature so that when you're running a brainstorming session, you're not just sitting in awkward silence. We make sure that these features are being used at the rate that we would expect them to be.

We supplement our research with a benchmark study in which an external agency does an audit of our product versus our competitors. They have proprietary usability scores, and they give us a report card of sorts so that we can track different efforts to improve different parts of the product. It’s nice to have that external input every six months. One of the other benefits is they talk to a lot of people to get the data that they need. So we get really rich insights, which we can incorporate into our plans.

If internal feedback is saying something different than external feedback, how do you weigh those opinions?

It’s a big challenge. We try to make sure that internal users are “canaries in the coal mine” in the sense that they bring issues to our attention, but we don't necessarily sound the alarm all the time. If people from across the company are voicing the same concern, that might indicate a trend. But if just one person has a complaint, and it only seems to be impacting them, we will listen to their feedback and prioritize it against other things.

How do you balance the needs of different user personas like engineers and product managers?

One of the things that we always ask when we're writing a requirements document for a new product or a new feature is, “Who is this for?” We don't get hyper-specific, but we try to identify a business function and what people might be doing it for.

We find that with a digital whiteboard tool, there's a lot of overlap in terms of how people use it. There are features we build that are more targeted at facilitators (i.e., people who run a lot of meetings), for example, but they don’t compromise the experience for others. We just focus on being intentional about who we’re building for.

Can you speak to a time you’ve identified that something needed improvements and describe how you improved it?

I can tell you about one pretty humbling experience. For a while, we did not have a table functionality, which we knew was something people really wanted. In the meantime, we had a sort of workaround using sticky notes; users could import or paste data from a CSV into FigJam, and the tool would paste that as an array of sticky notes. When we finally replaced that workaround with the table features, we learned that a lot of people really liked that sticky functionality. So as we launched tables and were feeling super proud of it, we then got feedback that people missed that former functionality.

We put a decent amount of resources into finding a way to sort of support both of those cases. We ended up bringing the former functionality back in addition to the table feature. People were happy about it, and it was a good reminder that not every step in one direction is necessarily a net improvement for everybody. I think that goes back to, like you were saying, performance versus simplicity or usability. It’s more performant to support both of those use cases.

This interview was edited for brevity and clarity.