KPIs to drive product roadmap prioritization

To build a business model that can help your startup make waves in a crowded marketplace, consider Henrique Boregio’s approach: stop chasing “feature parity” and focus on creating something truly unique.

As CTO at Primephonic, the Amsterdam-based music streaming service sometimes called “the Spotify of classical music,” Henrique Boregio has channeled this approach into his company’s product roadmap, focusing his team and resources on building differentiated features for the niche market segment.

In the latest installment of our Metrics that Matter series, we’ll learn:

- How changing their North Star metric helped Primephone finetune its offering

- How the company personalized its approach for their niche demographic

- How developing unconventional personas helped them achieve an 80% conversion rate

- Why taking product risks is better than managing “feature parity”

What is your North Star metric and how has it changed over time?

When we started out as a business, we didn’t have any analytics in place. At that point, I’d say our metric was a “hunch.”

When we first implemented Mixpanel, we were mostly looking at monthly active users and daily active users—things that could tell us whether people were using the app. But that didn’t really move the needle in terms of getting us to the next level. Here’s why.

The Primephonic app is available in Web, iOS, and Android. But we also started to implement different providers, and integrations with smart speakers like Sonos and Chromecast. That means we were getting value from Primephonic without people necessarily being in the app. That made us think about how we could change the metrics—and then we figured out that, at the end of the day, we don’t really care if people come to the app as long as they can get what they want, which is, ultimately, to enjoy classical music.

When we realized that, we changed our primary metric to be media minutes consumed. How much audio is being consumed by our users daily, monthly, on average, etc.?

Now, with every new feature we push out to users, we make sure the “media minutes consumed” number stays flat or goes up. That’s the number-one metric for us at the moment.

How has your business changed over time?

We officially launched in September 2018. We had a soft launch in the Netherlands, the US, and the UK, just to measure if there was a market fit or if there was even interest in the product. That turned out to be quite positive. About six months later, we released to the rest of Europe, and a couple of months after that we released worldwide. Right now we’re available in about 150 countries.

How did you get your initial traction, your first users?

For the first few months, we spent no budget on marketing. Classical music is a very niche industry—it’s easy to get PR for new products and services; we were featured in a lot of online and offline publications, so the initial spike of users came in pretty fast.

Over time, we realized that we needed to get a better grip on the users coming in. We saw a massive flow of users, but they were not all necessarily our target audience. They were going to download the app and use it, but not necessarily subscribe. Right around that point, we started looking more into analytics to really understand.

You see people downloading, that’s good. You see people using the app but not really converting. So that’s when we realized that we needed to understand who these users are on both sides. Why are they not subscribing? But also, why are they subscribing? What do they actually want? Because, for the most part, I think, we’re still seeing this as a second subscription.

It’s rare to find users who listen exclusively to classical music. Usually, we’re a second subscription on top of some other streaming music. So we really do need to understand what the trigger is to get somebody to even acquire a second subscription.

As you began to use analytics, did you see any correlation between demographics and propensity to either become loyal users or upgrade?

In our first phase, when we were available only in the UK, Netherlands and US, we did split up the conversion numbers according to country—and they were all much the same. That’s also partly due to the fact that we curate content that’s pretty wide; our homepage features manually curated playlists that target all demographics. Things changed when we launched in 150 countries worldwide. Now, we can see that the country-specific conversion numbers are very different. For example, in the Latin American countries there’s a huge interest in classical music, but it’s not common for people to pay a subscription. When we lowered our prices in those countries, we started to see conversion levels closer to those of Europe and the US.

Analytics helped here, too. We were seeing that the conversion numbers were really low in those countries, even though the interest was there. We tested whether and how different pricing models—monthly/annual subscription, voucher codes, free trial periods, refer-a-friend—affect conversion. We’re able to make cohorts out of those users, and to see whether a user entering through a voucher code is a better or worse converter, two months from now, three months from now, etc.

What was involved in launching globally?

We decided for the sake of speed that we would not be providing localized content from day 1. It is suboptimal to launch in a country if you’re not available in those languages, and we knew, of course, that conversion levels would be lower because of this. But we also believe that if you really want to make a “big bang” kind of product, it’s not only about the copy, it’s also about the content. We went for a lightweight strategy.

The moment we launched, we could see in Mixpanel which demographics were picking up. Countries like Italy, France, and Spain immediately popped up, which surprised us because we had this feeling that they wouldn’t be too fond of having to negotiate the English language on the site. We were also being picked up by media publications in those countries, which gave us the numbers necessary to say, “Okay, so we’re not going to have a global marketing strategy, we’re going to actively spend money only on countries where there’s already organic growth.” We could clearly see that in Mixpanel.

Taking key metrics by country, we could see that it was very quickly going up. It was good in that sense, because right around that point analytics became something used not just by our tech department to see whether features are being used, but by other parts of the company, like marketing, which now sees Mixpanel as something that they actively need to look at to determine areas of marketing spend.

Why doesn’t your audience care so much about localization?

Most of our users are age 55 plus and are highly educated and relatively well off. We joke in the office that we don’t know whether you start liking classical music and then you become wealthy, or if it’s the other way around.

Unlike most apps, you don’t ask your users to add credit card information when they sign up for your 14-day “no card, no commitment” trial. Why?

Most of our users are okay with subscribing to a service with a credit card. What makes it hard is that music streaming has been around for a decade, and when people come to Primephonic, it’s because they’re not satisfied with one of the other streaming providers (like Spotify or Apple). People come to Primephonic with the bar set really, really high. So we see people being very demanding in terms of features; for example, they have this unique brand of audio device in their home and we don’t have native integration with that because about 0.1% of people own something like that.

Our goal has always been, first and foremost, to build a product that solves a real need for these users. We’ve made a very clear decision to keep credit cards out of the signup process. And yes, that has a negative impact on our conversion numbers: the people that you let through the funnel are not as qualified as somebody who enters their credit card.

If we were to add a credit card, like a paywall, or a credit card wall on top of our funnel, our conversion numbers would immediately just jump, because we’d be blocking those uninterested people right up front. On the flip side, that’s also just a very crappy user experience. We’re still a startup. We need to prove that we’re worthy of your credit card before we ask for it.

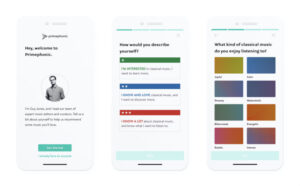

Tell us about your onboarding flow. What tradeoffs did you make by asking the questions you ask? For example, instead of age and other standard information, you ask about level of familiarity with classical music and favourite style of music (like “peaceful” or “dreamy”)?.

We built the onboarding experience around very specific needs or answers that we wanted. We do a lot of live interviews with users. We invite them to the office, we talk to them. Sometimes we test new features with them. Sometimes we just want to hear them out. Why did they subscribe? Why did they cancel?

From talking to many users, we were able to identify three personas, which we call Daniel, Elizabeth, and Charles. Basically beginner, intermediate, and advanced.

So we thought about how to determine what a Daniel might do in the app that an Elizabeth wouldn’t do. We built the onboarding flow specifically with that in mind. The first question we ask is how the user would rate themselves—as a beginner, intermediate, or advanced.

We propagate that one user property through everything that the user does in the app. The questions that the user gets are focused and, at the end of the onboarding flow, they get something tailor-made to their preferences. The first thing that really helped out was to get confirmation that we actually do have three different types of personas that behave differently. One very clear example that we can see is that conversion levels for advanced users are higher. Because, of course, they’re more qualified users, so the conversions are higher.

A lot more beginners join the platform, but they convert last. And in terms of content consumption, that’s also something that we can very clearly track in Mixpanel. The beginners usually consume a lot of pre-made playlists that we create and update every couple of days, and we also have playlists that we create based on data we get from Mixpanel. For example, we pushed out a beginner podcast about a month ago, starting with things like “What is classical music? What is Mozart? What is the Baroque period?” We were actually able to see that the beginners were interested not only in listening to music, but also in learning more about music. If you’re not deep, deep into classical music, you don’t know what to listen for. You need to know where to start.

Looking at the personas helped us define our product strategy as well as the content strategy. We had three or four different iterations of that onboarding process; we went from 20%, 25%, 26% to almost 80% conversion rate, from completion of the signup flow. That was good because we got our numbers up, and we also learned quite a bit about our users.

“Music consumed” is going up because of features that require fewer interactions for the user to play music. With the release of our latest Radio feature, users only need a couple of clicks to get five hours of uninterrupted music. We can see the impact of a feature also being pushed up to the higher metrics that we usually look out for.

How do you approach user interviews and incorporate qualitative feedback into your product roadmap prioritization?

The good thing for us is that three-quarters of the company is somehow involved with classical music.

For example, one of our customer experience representatives is a composer. Our head of curation is also a conductor. Everybody plays at least one instrument and most have had formal music studies. They’re also heavy users of the app. So we have a user group of about 40 people—40 people who have an opinion on every single product decision that we make. We always have quick access to real users just around the corner, in our offices.

It’s very rare that we start with a vague idea about “maybe it would be interesting to do this or that.” Ideas usually emerge from the people in the office. That gives us a starting point and then we start talking to users and seeing if there really is a fit. Usually, what we see is that our tensions are always between the beginner and the advanced users. Sometimes they clash quite a lot. Beginner users just want to be educated; advanced classical music listeners tend to be more skeptical about a service that provides recommendations.”Yeah, I know, I’ve been listening to classical music for 50 years, a two-year-old startup is going to tell me what I like.” We’ve actually been able to convince a lot of people because of the classical music that we have in-house. Whenever we’re working on a feature, we do need to really think: How is this feature going to impact the beginner? How is this going to impact the advanced user? We try to bring value to everyone, but sometimes it’s not perfectly balanced.

In terms of prioritization, we separate “needle-mover” features from “nice-to-haves.” For example, we see integration with other hardware as a “nice-to-have.” Yes, we will be disappointing some users. If 5% of our users are asking for a Bose integration, and we say no to that—it’s not nice for them. But what we’re doing right now is building features that will make a big impact on most users. We’re not going after the 3%. We’re going after the 10-15% increase. That’s more risky, because you can get that 10-15% on the negative side and really push out big features that nobody cares about. A good example of a big feature is one we released about a month ago: on-demand Radio. We gave it really a prominent place in the app, so that it’s one of the four or five tabs that you see when you open the app.

You’ve been an entrepreneur for a while. What have you learned about the user lifecycle—activation, engagement, and retention strategies—that you’re applying right now?

I’ve worked for other companies before where it was okay to identify patterns or actions executed by users who convert and then try to push people towards that by gamification, or by incentives.

We try not to do that. We’re partially going for the 55 plus market, so we think we need to make our UI very clear. Hiding features or adding a discovery component just won’t work because people will feel lost. We discarded things like gamification from the start.

We see that we can retain users if we can talk at the same level. We have classical music experts on our customer service team. That means the level of conversations that customers have with our users are at a much different level than if they contacted Amazon about a missing package. That personal aspect in customer service helps retain users and we’ve made product changes to reflect that. For example, the playlists we create are accompanied by the name and photo of the curator. Over time, people start liking specific curators. Having that personal aspect contradicts the way other industries are moving into fully automated recommendations, artificial intelligence, machine learning. Of course, we’re also building that sort of automation which helps us scale the business, but we are never going to completely get rid of the human touch.

Our service is kind of like a wine recommendation. Yes, you can read the label on a bottle of wine. You can fall in love with that wine, but you are also looking for somebody to tell you it’s good—and why. So if you have somebody that’s knowledgeable and tells you, “you want this for these reasons,” that’s something that users actively congratulate us on, and most of the reviews that we get on the App Store are usually also related to that manual content. That’s something that has a high impact on retention, especially for the more advanced users.