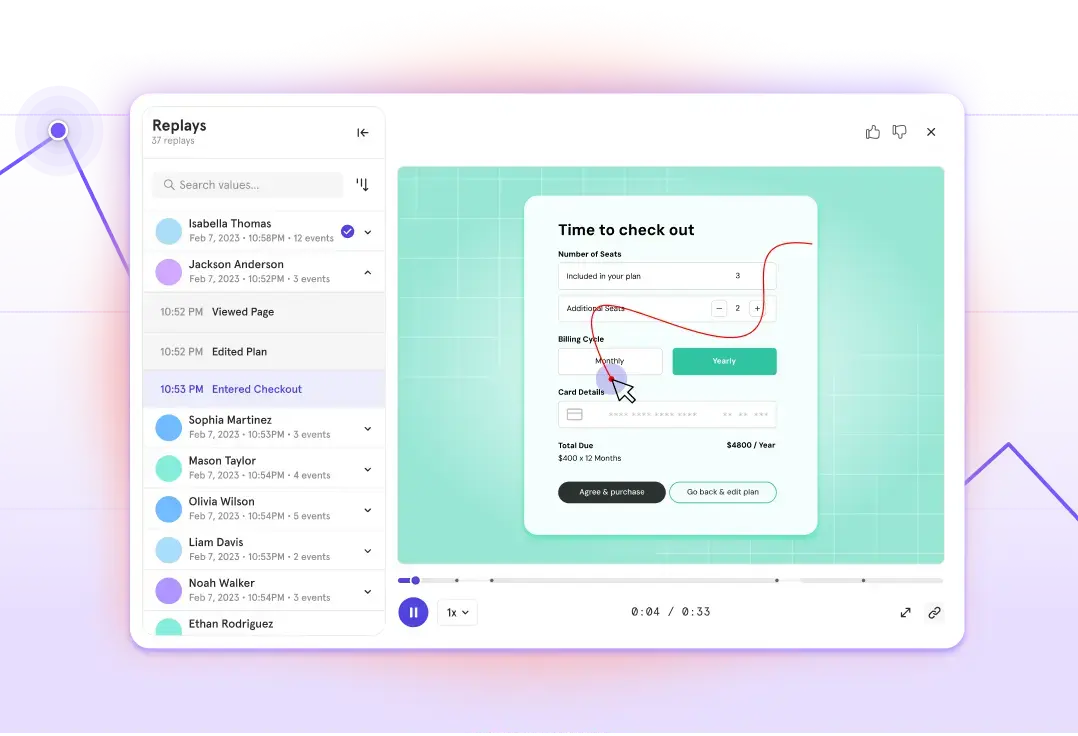

Sean Ellis on how growth hacking will outlive the hype

If you haven’t been living under a rock somewhere in Silicon Valley, you’ve heard plenty of people champion the ideas of “growth” and “growth hacking”. After all, there’s no success in tech if graphs aren’t up and to the right. But we’ve reached a point where companies are so focused on that idea of “growth” that it’s lost all meaning, so we have to ask:

Is growth hacking played out?

Sean Ellis doesn’t think so. The first marketer at Dropbox and now founder and CEO of GrowthHackers.com coined the term “growth hacking” seven years ago to describe a new way to do marketing. Tired of jargon-laden marketingspeak, Sean wanted to clear the clutter and figure out a framework for growth that was both testable and scaleable.

“The definition of growth hacking was actually based more on the definition of what growth hacking is not,” says Sean.

But let’s be real here: “growth hacking”, or anything-hacking, really, sounds cheap. It is itself becoming a victim of jargon, thanks to its most enthusiastic fans. A quick glance at r/entrepreneurs, or even GrowthHackers.com, reveals countless well-meaning “quick tips” and listicles that have resulted in “growth hacking” fatigue.

Sean Ellis knows this. He’s spent the better part of a decade getting literal-minded techies to love the idea of growth, and he still believes there’s more promise in the practice. He believes growth remains as important to a company as engineering, product design, or product/market fit. But not everyone realizes that.

“You can’t get educated until you realize you’re uneducated,” Sean tells me on a sunny late afternoon in SoMa. He’s such an easygoing guy that it’s easy to forget that he’s led successful early marketing teams at LogMeIn, Eventbrite and, most notably, at Dropbox. His job today is to help tech reconsider growth hacking.

“I think that the definition of growth hacking in people’s heads needs to change,” Sean says. “I think right now, outside of marketing and growth teams, the perception of growth is that it’s the ‘bad’ of companies. It’s the Ginsu knife commercials; it’s the cheesy and spammy stuff that you add on top of a beautiful product.”

This is not mere rebranding for growth hacking; this is a refocusing of the relationship between product and growth, where product creates the market potential and growth fulfills that potential.

Building a culture of experimentation (and being accountable for the results of those experiments) is the most crucial element when building a company focused on growth.

Let’s look into that. Are we in a post-marketing plan world? What does it really mean to get an entire company to think like a growth hacker?

What people get wrong about growth hacking

“Growth hacking is about running smart experiments to drive growth within your business. Marketing is about experimentation to move growth as well,” says Sean. “The problem is that marketing is also about a lot of other things.”

Traditional marketing is focused on driving brand awareness. It uses more qualitative metrics to measure success. Growth hacking (also called “growth marketing”) differs from traditional marketing by creating a company-wide culture of experimentation to move both key qualitative and quantitative business metrics.

Despite the way growth hacking has infused into Silicon Valley culture, most engineers don’t trust marketers, and for good reason. Traditional marketers in tech tended to be unable to tie their efforts back to the bottom line, and so engineers were just supposed to trust that marketing worked. That’s antithetical to being data-driven, of course, as witnessed from the failures of the big Silicon Valley marketing spends of days past.

“Most of the things that most traditional marketers do are not really scrutinized by their impact on growth,” Sean admits.

Startups have to think about product and growth of that product all the time. “Startups basically have to identify the right customers, acquire those customers, get them using the product in the right way, and figure out how to do that a whole bunch of times,” says Sean.

Tech tends to have a “product first, marketing later (when we have to)” mindset, or at least operates with the belief that a great product is undeniable, and so marketing shouldn’t be necessary.

Growth hacking actually works to bridge that gap between marketing and product by fulfilling the promise in the marketplace that a product creates.

According to Sean, product without growth has no impact on the problem that its founders initially set out to solve. It’s not until an effective product has rapid growth that the business actually makes a dent in the problem. Simply put:

Product + growth = impact

When a company starts to think about the importance of impact, it’s a lot easier for the entire team to rally around growth. And growth accelerates when the team starts to experiment.

In order to get an entire organization to experiment and see the value in experimentation, says Sean, every employee needs to not only question the way things are done, but also prove that successful systems can only take you so far. You have to break a model in order to reach higher goals.

From hype to experimentation

Growth starts with experimentation. Because, here’s the thing: you just don’t know how people are going to react to changes in the product, and so you must test your assumptions.

“Experimentation means finding and actually measuring what your customers love,” says Sean. You can make educated guesses, but to get real growth those guesses need to be proven out on real users.

“It’s asking, how do I apply my experimentation against the best opportunities in market? The motivations that drive people to try the product and keep using the product? How would we map all of that out and where do we focus those efforts?

“The biggest difference between companies that are growing or not is the ones that are running experiments tend to be growing.”

“At the very least, we must hold ourselves accountable to the number of experiments we run each week so that we’re not in ‘paralysis by analysis.’ We must actually do the things that are going to improve the results.”

How many experiments? Just start somewhere, anywhere. It’s harder to go from no experiments to even three per week; it’s much easier to tweak bad experiments into good.

“It’s not a big leap to start doing it well,” Sean says. “You do develop muscle memory and get smarter about how to do these things over time, but ultimately you never get smart enough to know the answers in advance on experiments.”

The biggest experiment, ever

One of the biggest experiments Sean ever ran was as the founder and CEO of Qualaroo, a customer surveying SaaS startup. He asked the board of directors to make a bet on expanding market presence by significantly improving the free version in their freemium platform.

This was a model that he’d seen work many times before; people could use their customer surveys for free if they retained the “Powered by Qualaroo” badge. In this way, every survey that popped up across the internet was an ad for the company.

“Our interpretation of the growth model was that the ‘Powered by Qualaroo’ branding was the main thing that was driving growth within the product.

“We reasoned that the more times that that was out across the web, that meant more ‘ads’ being run so, if we made the free version a lot better, that would lead to a much bigger footprint. We thought we’d reduce our overall conversion to premium, but would be on a much better, stronger growth trajectory because of increased demand for the free version. Talk about a big bet!

“It turns out that better free version didn’t significantly increase overall demand for Qualaroo. It did however reduce the number of people that wanted to pay for the premium version (free was good enough for most of them).

“We could’ve considered that a total failure, but we went the other direction and we said, ‘What did we just learn from that failed experiment?’ We learned there’s very little price sensitivity on this product, and very little price sensitivity is a good thing! We killed the free version completely.

“We really started investing in product a lot more, kept raising the price over time, and completely re-engineered the product and made it something that validated that premium price. Pricing became our most important growth lever in that business. That was the discovery that we got off of the failed experiment.”

With more testing comes the opportunity for more discovery and more optimization, and more ways to reveal opportunities from “failures.”

“I’ve written many blog posts around the importance of freemium,” Sean explains with a chuckle. “It was awesome for Dropbox. It was awesome for LogMeIn. But I think the key to any of this is that the prevailing wisdom does not apply in any of these things. Each business is unique. That’s why you have to understand the needs of the market, how they’re going to respond to things.

“The better you understand your growth model, the easier it is

to come up with the right experiments to run to improve your key metrics.”

“Anybody who understands growth well knows that you probably should put around 50% of your product development resources into onboarding on an ongoing basis,” says Sean, fully aware how shocking 50% is to an engineer or an engineering-minded founder.

“If customers ultimately don’t have a good first experience with your product, there is no second experience.” It’s hard to argue with that, but many in an org will be skeptical. This isn’t easy because growth isn’t always the default mindset.

If you’re the first growth marketer at a company, there are ways to get buy-in and to avoid the most common growth pitfalls, without going through a trial-by-fire like Sean did.

Part Two of our profile on Sean Ellis continues here, and focuses on how Sean sees the future of growth, why paid customer acquisition never works, and how growth marketers can get buy-in from everyone at their company. To make sure you get all of our articles first, sign up below for The Signal’s newsletter!

Photographs are courtesy of Sean Ellis, GrowthHackers.com and DTTSP/Kim Wouters.