Sorry, it’s time to pivot: Hard truths about ‘good’ product metrics from a founder

As a founder, you have to be optimistic and believe in your product, even when others don’t. Founders’ lives are hard—we spend so much time at our computer, getting virtually beaten up by users whenever something breaks, trying to convince people to use our product and share our vision.

That’s why it’s good to be a little delusional about our product. It certainly helped us get started when we launched a fairly audacious app idea in Stompers.

But founders also need to be ruthless about our metrics.

I’ve seen too many founders trick themselves into thinking their metrics are going to improve dramatically or, even worse, focus on the wrong numbers to convince themselves a product will take off.

I know, because I was one of them.

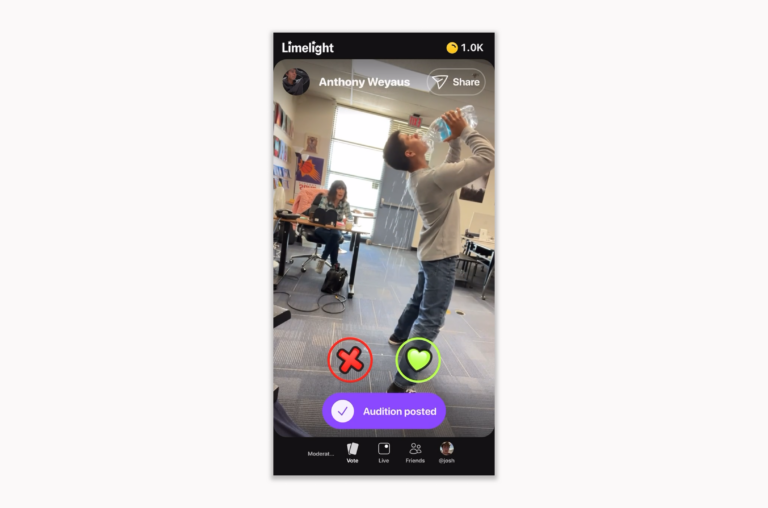

When I built one of my first apps, a livestreaming social media platform called Limelight, I started with an inherently viral concept: What if one person were famous every day?

Limelight would randomly choose one person every day to live stream to everyone else—ensuring that any member, at any time, might get their 15 minutes of fame. The app was only live for a few minutes each day and required users to log in during that specific window.

When I first started marketing Limelight, within weeks I had TikToks about the app hitting several million views. This was a great indication of interest, maybe even an early sign of getting closer to product-market fit, I thought.

The reality was much more complicated.

Product-market fit: Don’t eyeball it—measure it

Like a lot of founders, I let shiny vanity metrics like TikTok views give me hope for Limelight. (Founders need optimism, remember?)

But I'm also a deeply data-driven person. I knew that things like engagement, virality, and especially retention mattered more than TikTok views.

People tell founders not to look at the numbers in the early stages. In my opinion, that’s a mistake, especially for a social app.

Social sharing metrics like how many friends people add can make or break a social app—people want to be where their friends are.

Long-term retention and stickiness metrics show that people are getting consistent, ongoing value from your product.

And those numbers were less optimistic.

I believed in the product, and I wanted to bring it to life. But it felt like work. Users were leaving, and I had trouble retaining them.

For one thing, putting a random person “on stage” every day the way Limelight did carried a lot of risk. Not everyone wants to entertain a crowd, and moderation could get tricky (as you can probably imagine).

The truth that we needed to learn—and that I now tell other founders—is that you need to be realistic about the level of engagement and usage you can expect from people.

Take Instagram as an example: Most people on Instagram check their feed, post occasionally, and watch a few stories. It’s the 1% of users who create content that keep the platform running.

It’s the same with a restaurant review website: The vast majority of users will read the reviews, but only a tiny fraction will actually write them. If your product relies on everyone to behave like that 1%, you’re going to have a rough time. Founders need to adjust their mindset and expectations of how people will actually engage with their product.

And that’s exactly the trap we fell into with Limelight. Our product had high expectations of user engagement and required unrealistic user habits.

Fortunately, because we are data-driven people, we were able to look at the numbers and learn from our experience. We saw that our retention, especially our long-term retention, wasn’t where it needed to be.

And we were able to use what we learned to pivot.

Being realistic about what you can change

Retention, and long-term retention in particular, is a very difficult needle to move. Founders should be realistic about how much iteration can improve things. Even a very successful product like Duolingo will fight to improve retention by single-digit percentages.

That’s why I tell founders to be ruthless when it comes to analyzing their data.

If by your first 1,000 users you have day-one retention of 10%, you can really only expect to move that by 50% or 100% (so up to 20% day-1 retention) if you’re very lucky. You’re not going to 10x your retention no matter how much you iterate. You can’t A/B test your way to product-market fit.

Limelight vs. Stompers: A tale of two startups

As I mentioned above, we had unrealistic expectations of user engagement when we built Limelight. Scaling from 0 to 1 was a very interesting challenge, and there were a lot of valuable lessons learned. In a lot of ways, Limelight set the foundation for Stompers.

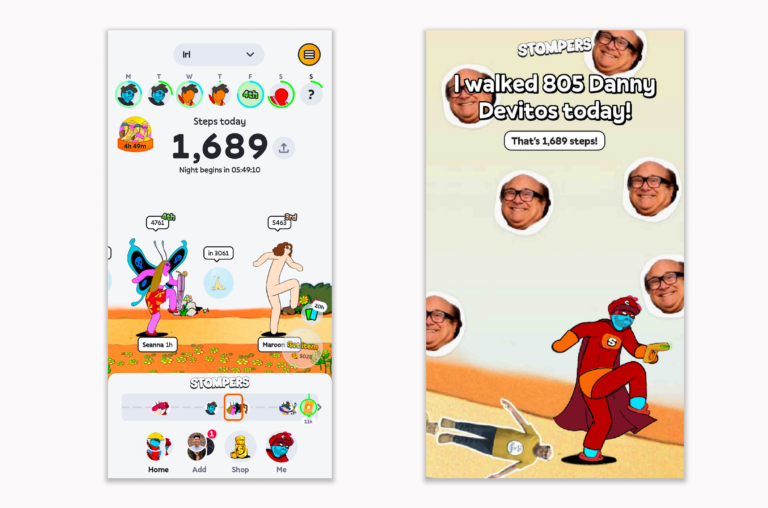

When my co-founder pitched me the idea about Stompers, one of the key differences we knew we wanted was to make it easy for people to engage in a lightweight way. Limelight required too much from too many of our users.

Stompers is a competitive step-tracking app, which might sound like an idea without a market. But we’ve found that users really get invested through challenging friends, creating a “Stomper” avatar, inviting friends, winning items, and making in-app purchases. And almost more importantly, Stompers doesn't expect to take over a massive attention black hole like TikTok. Users don’t even need to open the app very often to interact with the ecosystem: Their phone is automatically tracking their steps.

Even though we had a low-key launch, Stompers took off on its own by word of mouth—with barely any marketing. Even some of my elementary school friends I hadn't spoken to in years were signing up.

The difference from Limelight was immediate. With Limelight, we felt like we were fighting an uphill battle to improve retention and increase our user base. With Stompers, we needed all hands on deck to keep up with the momentum the product generated organically. Very quickly, there were users on Stompers who had more friends than I do, who were more engaged with our product than we were. It was growing on its own. We weren’t the ones driving the growth.

You can’t quantify word of mouth, but looking at social sharing metrics and retention data helped us see that Stompers had clear growth potential.

Your metrics won’t lie to you, so why would you lie to yourself?

As founders, we invest years of our lives into products that we believe in, and we know that the odds of building a product that becomes massive are slim. Lying to yourself about a product’s chance of success is only keeping you from pivoting to a different idea—one that might have a better chance at success.

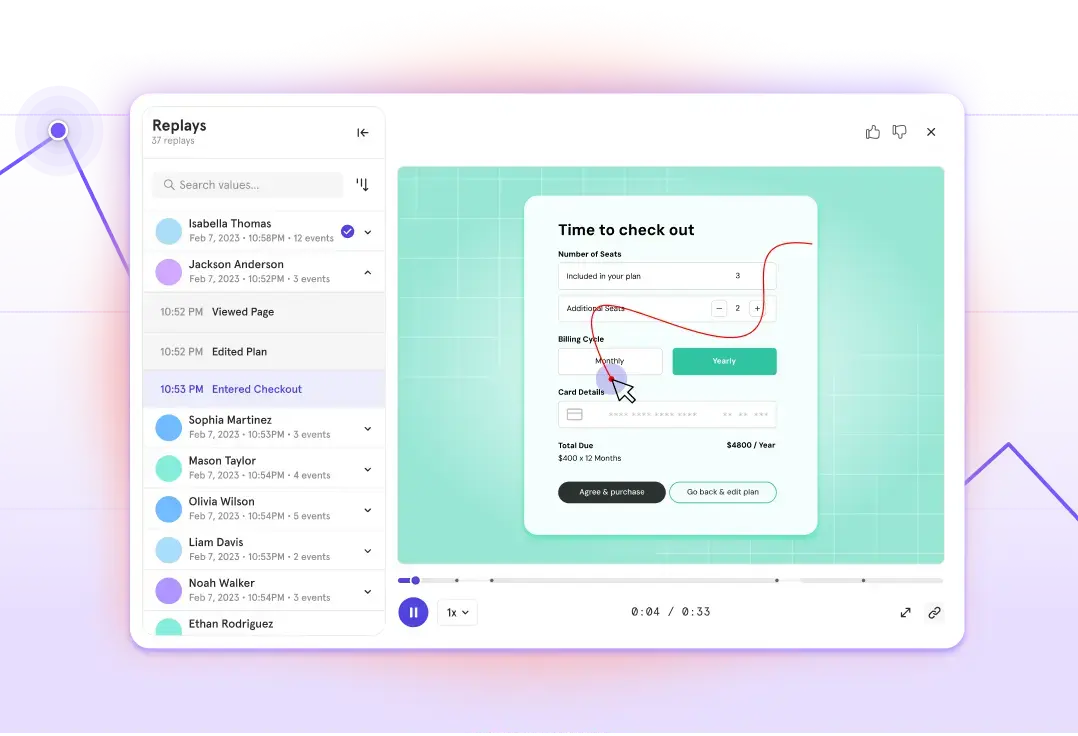

So dig deep into your data. I’ve always used Mixpanel for this, especially for building cohorts and segmentation to understand your users. Be ruthlessly honest with yourself about your retention metrics and product stickiness, how much you’re going to be able to improve those numbers, and whether that will be enough for what you want to achieve. Make sure the data you’re looking at is accurate and high-quality, especially when you’re looking at a small sample size of users.

Your data won’t lie to you, so don’t use it to lie to yourself.